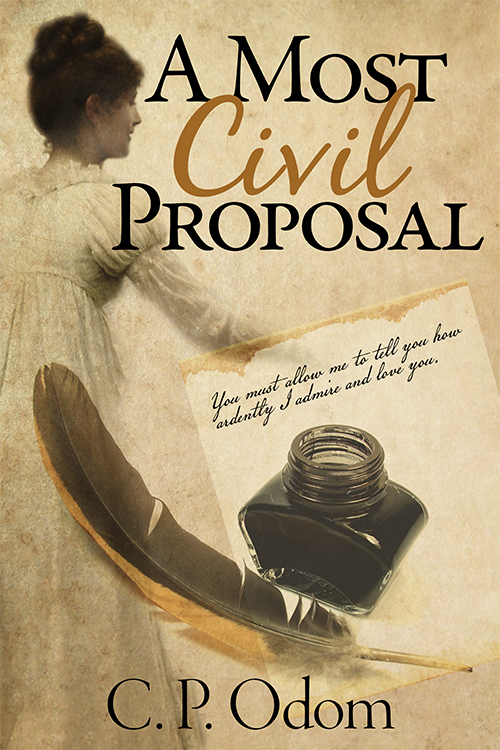

A Most Civil Proposal

AMCP About

You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.

When Fitzwilliam Darcy spoke these words to Elizabeth Bennet as part of his marriage proposal, they expressed his concealed feelings completely, but their meaning was at odds with the rest of his prideful and arrogant offer of marriage. It was therefore rather easy for Elizabeth to reject his offer in much the same manner. But what if Darcy, never one at ease when trying to speak of inner sentiments, had realized beforehand how his intended proposal would sound to the young woman he hoped to make his bride? What if he had attempted a much more civil and thoughtful proposal of marriage? Could Elizabeth Bennet have coldly and angrily rejected an offer made in such a manner? A Most Civil Proposal, a variation on Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, examines and explores how the lives of the two main characters and their families and friends might have turned out differently had Darcy realized his error beforehand and thus avoided being so forcefully instructed and corrected by the love of his life.

- A Most Civil Proposal By C P Odom

- ISBN 1936009218

- Status Published February 21, 2013

AMCP Prologue

Wednesday, April 8, 1812

“Will that be all for tonight, Mr. Darcy?”

Fitzwilliam Darcy, lost in the turmoil of his thoughts, turned from the window to find that his valet had completed preparations for the morrow.

“Yes, Jennings,” replied Darcy absently, “thank you. That will be all, and I wish you good night.”

“Will you be rising as usual tomorrow?”

“Yes. As usual.” Darcy turned back to the window.

“Then I wish you good night also, sir,” said his valet, and the click of the closing door followed shortly.

Darcy again tried to concentrate. He was coming to the conclusion that it was nigh impossible to determine just how his well-ordered and well-planned life had descended into the tumult and uncertainty that plagued him at present. As recently as the previous day, he had been firm in the belief that his emotions were well in hand, that his detachment was still in place, that he was . . . safe. Safe from the bewitchment of Elizabeth Bennet, secure in his position in society, and fixed in his confidence as the master of his own fate.

And now? Now he knew that safety had been only an illusion and that he had actually stepped well over the edge of the precipice before being fully aware of the danger. At what point had it happened? Was it during his walk with her in Rosings park the day before? Perhaps — or perhaps not; it did not matter. He knew only that his present resolve to speak to Miss Bennet on the morrow was as real as his previous resolve to ignore her had been imaginary.

He snorted. Speak to her? No, it was much more significant than that. He would make an offer of marriage to her despite the humiliation and strife that would result. He, the master of Pemberley, and she, the daughter of a country gentleman of small fortune and no connections! But it did not matter anymore, and he could not determine when that point had been reached.

The mistress of Rosings, his aunt Lady Catherine de Bourgh would not be pleased. The thwarting of her long-held ambition to align himself with his cousin Anne de Bourgh and to join Pemberley with Rosings would not make her temperate. She was well used to having her own way, and he had walked carefully in past visits, remaining non-committal without overtly contradicting her oft-expressed plans. Indeed, they had derived considerable amusement as he deftly sidestepped her mother’s blunt suggestions. It had seemed harmless fun then since neither of them had any wish to marry. In fact, Anne had told him many times that she knew her health never would allow any kind of marriage, and she would be happy to live out her life quietly in a modest country estate rather than Rosings. But Anne’s wishes were meaningless to his aunt, and when Lady Catherine learned of his engagement to Elizabeth Bennet, she would be outraged beyond measure.

“It will not do,” he said aloud, picturing Elizabeth’s face crumpling under the onslaught of her ladyship’s disdain. Then he snorted again, this time in amusement. Miss Bennet had already demonstrated her ability to stand up to his aunt — never retreating yet never quite offering offence. Impertinence it might be called, but courage it could also be named, and he cherished that quality as he imagined her at his side, one eyebrow arched in amusement while Lady Catherine thundered and raged ineffectually.

While his aunt’s reaction boded to be extreme and predictable, Darcy was none too sure about the rest of his family and friends. He well knew his uncle Lord Matlock would not be pleased, but just exactly what his response might be was not certain. He took his position as the head of the family seriously, and he would not be happy about a match between the Darcy name and fortune and a country girl with little to bring to the marriage.

His jaw clenched, and his brows knit together in determination; for the thought of Miss Bennet being abused — of his allowing her to be abused — was too painful to consider. “I will not allow any mistreatment from my relations,” he pledged aloud. “None!”

Now the subject that had gripped his thoughts all evening returned anew. How would he address her? He planned to take the opportunity the next day since his aunt’s parson and Elizabeth’s cousin, Mr. Collins, and his guests were invited to take tea at Rosings. His cousin Colonel Richard Fitzwilliam had urged the invitation, noting it would be the last chance before their departure on Saturday. Darcy could not determine whether his cousin suspected his attachment to Miss Bennet, but Fitzwilliam’s amiable attentions to her had played no small part in forming Darcy’s resolve. Despite Richard’s need to pay at least some notice to money when he married, Darcy was decidedly uncomfortable both with Richard’s ease with the lady and with her own response. He wished again that, just once, he could conduct a conversation with her without saying something he did not intend and often did not mean. Much as he enjoyed her verbal repartee, it made him more than a little uncomfortable that many of their exchanges resulted from statements that he never would have previously believed could fall from his lips. Unwillingly, his own words echoed in his mind: “But pride — where there is a real superiority of mind, pride will be always under good regulation.”

“Idiot!” he groaned in mortification. Even though he could not fault the sense of the statement, how could he have made such an immodest declaration aloud and in company? He had always despised such boasting by other men, and he remembered the night at Netherfield as those words tumbled from his mouth without thought. He cringed inwardly as he also remembered her turning away to hide her smile — yet another joust won by Miss Bennet.

At least it will be finished after tomorrow! Then he could speak of emotions and thoughts that could not be talked of until he declared himself. Fleetingly, he wondered whether he should proceed with more caution, perhaps a simple statement of his esteem and desire to court her in the usual manner, but his inner tumult was such that he rejected the idea almost before it presented itself to his mind. Her wits were much too quick for such discretion; she, of course, must know of his regard for her. He would not disappoint her with a tepid request for courtship when his own fervent love asserted, nay required, a clear declaration of intent. After tomorrow, all will be complete.

Remembrance of earlier missteps, however, now added to his discontent. This was too important to leave to chance. He could not afford to make a hash of the fundamental step of proposing marriage when he had, on previous occasions, so oft been unable to manage even simple conversation. A plan of action was called for. Pacing in agitation in front of the fireplace, he imagined himself facing Elizabeth after suggesting a walk through the formal gardens after tea. After seating her on one of the benches in the garden, he was facing her… he was opening his mouth . . .

In vain have I struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me —

He stopped short and groaned as the words sounded in his mind. He could almost see Miss Bennet looking up, first in surprise at his usual inability to speak clearly and then in disbelief as he testified to his inward struggles. Should he not simply say he loved her beyond measure instead of starting out by saying he did not want to love her? Such explanations were unnecessary and, though true, could be construed as insulting since she was as cognizant of the disparity between their stations as he. His attraction to her was clear, and she must also be aware that those distinctions no longer mattered.

He resumed pacing, increasingly convinced that he would be unable to speak to her at all. His agitation increased as a sudden vision came to mind: he struggled to speak, he could not, and he turned to flee the garden, leaving Elizabeth behind in growing distress at being abandoned.

He closed his eyes. I must do this right!

As he paced, his eyes swept over the writing desk and the sheets of stationery upon it, and he halted, struck by the memory of his time at Cambridge. Then, too, he had faced difficulties in presenting the results of his studies in the presence of his more easily spoken fellows. But he had been driven to overcome this perceived inadequacy on his part, and he had learned to compensate by preparing himself before his verbal addresses, marshalling his thoughts by committing them to paper, and subjecting them to rigorous analysis before giving them voice. He had not had to perform similar preparation since completing his studies, but the scheme appeared tailor-made to deal with his present apprehension.

He lost no time in taking the candle to the desk and seating himself. Selecting a pen and pulling a sheet of stationery in front of him, he opened the inkwell, dipped his pen, and began:

Miss Bennet, you must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you . . .

Darcy leaned back, massaging his shoulders to work out the cramps after long hours spent in intense concentration. His feet were chilled as the fire had long ago died down, but he regarded the many pages before him with a measure of satisfaction. The scores of corrections and even the sentences that were entirely marked through did not cause him embarrassment; he actually felt relief at having properly set down his first thoughts and then subjecting them to intense scrutiny. He had spoken them aloud, judging their impact on the only audience that really mattered — Miss Bennet — and made his changes ruthlessly. Several crumpled pages littered the top of the desk when entire passages were rejected in favour of copying the one or two worthy sentences to a new sheet. He could not imagine the mortification that would have resulted had he delivered his sentiments with no preparation. Though it could have no impact, of course, on her acceptance, the embarrassment of presenting himself in such a manner was not to be considered.

Gathering the pages into order, he pulled out a fresh sheet of stationery. The only remaining task was to make a fair copy of the written thoughts and then to burn the offending sheets before trying to get a bit of sleep before dawn . . .

AMCP Chapter 1

Thursday, April 9, 1812

When Elizabeth returned to the Parsonage after walking with Colonel Fitzwilliam, she went directly to her room as soon as the colonel left them. There she could think without interruption of all he had told her, and she soon found her anger rising as Mr. Darcy’s interference between her sister Jane and Darcy’s friend Mr. Bingley became more apparent. She had heretofore attributed the principal design and arrangement of separating them to Miss Bingley, but Colonel Fitzwilliam’s disclosures now pointed to Mr. Darcy as the offending conspirator. When she thought of how his pride, caprice, and arrogance had destroyed the chance for happiness of the most affectionate and generous heart in the world, she felt the tears sting her eyes. Further consideration of the matter brought on a headache, which worsened so towards evening that she determined not to attend the cousins at Rosings, where they were engaged to drink tea. Her friend Charlotte Collins, seeing that she was quite unwell, did not press her to go and, to the extent possible, prevented her parson husband from prevailing on her to attend even though he could not conceal his apprehension of Lady Catherine’s being rather displeased by her staying at home.

When they were gone, Elizabeth, as if intending to exasperate herself as much as possible against Mr. Darcy, chose for her employment the examination of all the letters Jane had written to her since her being in Kent. They contained no actual complaint, nor was there any revival of past occurrences or any communication of present suffering. But in all and in almost every line of each, there was a want of that cheerfulness which had used to characterize her style and which, proceeding from the serenity of a mind at ease with itself and kindly disposed towards every one, had scarcely ever been clouded. Elizabeth noticed every sentence conveying the idea of uneasiness with an attention that it had hardly received on the first perusal. Mr. Darcy’s shameful boast to his cousin of what misery he had been able to inflict gave her a keener sense of her sister’s sufferings. It was some consolation to think that his visit to Rosings was to end on the day after next and a still greater consolation that she would be with Jane in less than a fortnight, able to contribute to the recovery of her spirits by all that affection could do.

She could not think of Darcy’s leaving Kent without remembering that his cousin was to go with him, but Colonel Fitzwilliam had made it clear that he had no intentions toward her at all, and agreeable as he was, she did not mean to be unhappy about him.

While settling this point, she was suddenly roused by the sound of the doorbell, and her spirits were a little fluttered by the idea of its being Colonel Fitzwilliam himself, who had once before called late in the evening and might now have come to inquire particularly after her. But this idea was soon banished, and her spirits were very differently affected when, to her utter amazement, she saw Mr. Darcy walk into the room.

Darcy had been surprised, nay he had been shocked, to discover that Elizabeth was not with the Parsonage party when they arrived for tea that evening. His preparations had been made, he had reviewed them in his mind, and he was comfortable with his planned approach. Now she had not attended, and he was thrown into disarray.

He wondered at her absence. She knew there was but one day before his departure. Could she truly be ill?

Sudden concern over her well-being replaced his anxiety, and he made an excuse to leave the room as soon as was practicable. He saw Fitzwilliam’s eyes raised in question, and he knew without having to look that her ladyship was not happy. In fact, he heard her loudly questioning his cousin as he exited the room: “Fitzwilliam! Where does my nephew go? Has he forgotten his duty to our guests?”

Any response that the colonel made was lost on Darcy as he went up the stairs and strode down the hallway to his room, surprising Jennings as he was laying out bedclothes and preparing for the morning.

“Mr. Darcy?”

“My hat and coat, Jennings,” Darcy demanded abruptly. The valet was clearly puzzled but said nothing as he quickly retrieved the coat and helped his master into it. He picked up a whisk, prepared to brush off the shoulders as usual, but Darcy was too impatient to wait. He waved Jennings off, snatched his gloves and hat from the bed, and turned for the door.

“Mr. Darcy, sir!” his valet exclaimed in distress.

“Yes?” he responded sharply, and Jennings swallowed at the impatient look on his face.

“Where shall you be if there are inquiries, sir?”

Darcy forced himself to calmness. Jennings could not know his intentions, but he had been with him too long not to recognize his employer’s uncharacteristic behaviour.

“If Lady Catherine asks, tell her that I am unwell and sought fresh air to alleviate my distress,” he said finally, his thoughts in such chaos that he found concentration nigh impossible.

“And if anyone else asks, sir?”

“Tell them whatever you please!”

The door closed abruptly as his footsteps echoed down the hall. Jennings remained standing, his mouth open in consternation as he stared after his departed employer, trying in vain to determine what could have brought about this agitated behaviour.

Even afterwards, Darcy could remember little of the rapid journey to the Parsonage until he rang the doorbell.

“Miss Bennet,” he told the surprised girl who answered the door. His stomach quivered in anticipation as she dropped a quick curtsey and then led him to the drawing room where the ladies habitually sat. Removing his hat and gloves while he followed, Darcy breathed deeply, trying to calm himself as he stepped into the room.

Miss Bennet looked up, the utmost surprise on her face, then stood to render a curtsey, and he was instantly lost. He had prepared himself, he knew what to say, and he knew how to say it, but suddenly his tongue cleaved to the roof of his mouth, and he could speak not a word. His admiration for her threatened to choke him, and he chastised himself savagely — Talk, you fool! Say something!

“Miss Bennet,” he finally forced out. “Mrs. Collins said you were feeling unwell. I thought . . . I thought to inquire whether you were feeling better.”

“I thank you for your concern, sir, and I have indeed improved,” she said in a tone of cold civility, and Darcy’s stomach tried to turn over at the tone of her voice.

Why is she so cold? he asked himself. Can she not see why I have come? Does she have no suspicion?

Darcy sat down, but he was still unable to speak. Suddenly, he could not remember any of what he had so carefully prepared, and he raged inwardly at being struck as dumb as the veriest dullard!

He stood and walked to the side of the room, to the window, and then back to his seat, his agitation increasing. Miss Bennet watched him silently, waiting and saying nothing. Abruptly, he remembered the papers in his pocket. As a student, his written preparations, placed carefully in a coat pocket, had served to give him the confidence to speak, but he had never needed to consult those notes. Their mere presence on his person had been sufficient, but in this instance, he suddenly knew that he required more assurance, and he at once pulled the papers from his coat and unfolded them.

As he looked at his written words, he felt a wave of calm sweep through his body. He closed his eyes in relief, and then, wasting no time, he began –

“Miss Bennet.”

Elizabeth looked up in renewed surprise at his words, but even more at his tone. Mr. Darcy had spoken her name with unaccustomed gentleness, almost as if he were caressing the words. She could not understand . . .

“Miss Bennet,” he continued as gently as before, “you must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.”

Elizabeth’s astonishment was beyond expression. She stared at him in shock and felt a blush mount her cheeks. She could not account for his words and said nothing in return, a fact that evidently provided sufficient encouragement, for he continued.

“From the earliest moments of our acquaintance…”

Elizabeth looked down demurely, staring at her hands in her lap.

“I was impressed by your lively spirits, your warm heart, and your ease with all you meet. The more I saw, the more I was attracted, especially as these attributes are so lacking in my own person. I was soon bewitched and utterly lost though I did not realize it at first. I remember when you first came to Netherfield to tend your sister, your petticoats stained with mud but your cheeks bright with exertion and your hair windblown and enticing.”

Darcy watched Elizabeth keenly as she sat with a blush on her cheeks, unable to meet his gaze.

“I must confess I first wondered — and almost hoped — that you had come because of me, but I was soon disabused of that base thought as your concern for your sister showed your true merit. I was so used to being the object of all manner of plots and artifice by almost every unmarried girl and their ambitious mothers that I was unprepared for your artless devotion to your sister. Your actions proved me utterly wrong then and not for the last time. But I also was deeply impressed by your wit and your spirit, and I quite enjoyed crossing verbal lances with you at Netherfield and again here at Rosings. Even though,” he said wryly, “I was more often forced to retire from the field in defeat than otherwise.”

He consulted his notes again and continued, “I cannot fix on the time or the place when I knew I loved you. I was in the middle before I knew that I had begun. But I soon began to imagine you every place I was wont to go: in my carriage, in my house in London, by my side at the theatre, and most especially at my home at Pemberley. When I saw you on your walks, I envisioned you on the many pathways at Pemberley. I saw you with Georgiana, being the sister that she never had, providing the advice and the example that I was not able to supply. I grew to realize that we could fit together well, that your liveliness would balance my reserved nature, and my knowledge and experience of the world, garnered over years of managing my own affairs, would work to your benefit.

“I know that I have not been able to speak clearly before now. Indeed, I have usually found myself so stricken in your presence that I have said what I did not intend and did not mean, and I have not been able to say that which I fully meant to say.” He frowned somewhat and then reddened slightly, looking again at his papers. “I have never been in love before — never even felt attraction before — and I know I have not presented myself to best effect. As you can see” — he waved his papers at her — “I was as speechless as ever until I retrieved my prepared notes. I have no skill at casual discourse, a talent so many others seem to exhibit with as little effort as breathing, a talent that I hope to improve upon in the future under your excellent tutelage. ”

Elizabeth looked up at that moment and felt a shock run through her as Mr. Darcy fixed her with an intense gaze that she suddenly realized had never been a glare of disapproval at all but the exact opposite. “I should have said more,” he continued, “but I can only say that a man who felt less might have done so.”

Taking a deep breath, he turned to the last page and continued, “There will be some who will raise objections to our match, who will make reference to the difference in our situations, to your lack of fortune, to your country origins. Some may come from my family,” and Elizabeth, looking up, was surprised by the fierceness of his expression. But he continued, his face softening, “and some may come from society in general. I cannot say at this time. But these objections are meaningless to me, and I will permit no one to abuse you in any way. I am my own master and need neither approval nor advice from my family in choosing whom I marry. I cannot pretend never to have entertained similar objections myself; I wish I could. But I have since confronted them and rejected them utterly. I cannot conceive of any woman more worthy to be at my side, more intelligent, witty, lively, courageous, and caring, and I know I can never love another as I love you. I beg you, Miss Bennet, to relieve my present distress and do me the honour of accepting my hand in marriage.”

Elizabeth was in a state beyond amazement. She had never imagined receiving a proposal of marriage in such a heartfelt, open, and touching manner from any man, and she was quite unable to explain having received it from Mr. Darcy. She could see that he had no doubt of a favourable answer; he spoke of apprehension and anxiety, but his countenance expressed real security, and though her intentions did not vary for an instant, she was sorry for the pain he was to receive. In spite of her deeply rooted dislike, as well as her smouldering anger due to his interference between Jane and Mr. Bingley, she could not be insensible to the compliment of such a man’s affection and could not respond with anything less than civility equal to his own. Composing herself, Elizabeth rejected several openings, before finally speaking.

“I must confess, sir, that I am most completely surprised at your sentiments.”

“Surprised?” He was clearly startled.

“Indeed, quite surprised.” She looked up and continued, “In cases such as these, it is, I believe, the established mode to express a sense of obligation for the feelings avowed, however unequally they may be returned.”

Darcy, leaning against the mantelpiece, stiffened and felt his calm composure shatter as the meaning of her words sent a thrill of disquiet through his chest. However unequally they may be returned? he thought in confusion. Dear God, what could she mean? She could not refuse me, could she?

“I do indeed feel a profound sense of gratitude at the sincerity and the emotion expressed in your declaration, and I am complimented by your assurances. I never expected to hear so eloquent a statement, and I am quite sincerely sorry to offer pain to anyone. But, sir,” she dropped her eyes back to her lap, “I am afraid that I must refuse your offer. I do fear that I cannot match your feelings, and I am convinced that a marriage occasioned by such unequal affections would render both parties unhappy in the extreme.”

Elizabeth could not bear to look up. He had shown a depth of feeling that she had never deemed possible, and she feared that the sight of pain on his face might well shake her resolve. Nevertheless, she was determined neither to yield nor to give vent to either anger or venom in light of his civilities though she would not waver in the light of her objections.

For his part, Darcy listened with a sense of confusion and of bleak despair; indeed, the anguish that rocked him was beyond anything he had ever experienced. The constricting sensation in his chest and throat increased as she spoke until it was difficult for him to draw even a ragged breath. Other emotions followed close behind — disbelief, shock, and then anger. He turned away, trying to find the reserve that had served him for so long, attempting to don the mask of indifference he had crafted over the years, but he found to his consternation that he could not resurrect what he had given up.

She refused me! He repeated the shocking words to himself again and yet again. After everything he had told her and everything she meant to him, she refused him and dismissed him with no explanation. It was not to be borne!

He opened his mouth in rage, but the rustling of the papers still in his hand distracted him. He looked at them, and his anger dissolved. At no time in his preparations had he anticipated failure, certainly not failure this extreme. He had imagined that he held all the advantages — that once he overcame his scruples and knew himself, all was finished and done. Several moments passed as he struggled to find composure.

Elizabeth sat in anxious anticipation, glancing up at Mr. Darcy’s rigid figure as he stared out the window in silence. She dreaded what was surely to come — the anger and recriminations that were the natural emotion of such a proud, arrogant man at meeting so cavalier a refusal. She opened her mouth to beg leave to return to her room, but before she could speak, he turned back to her. He had evidently regained some degree of equanimity, and he was able to continue with a measure of civility at odds with the anguish of his face.

“I beg leave to inquire as to the particulars of your refusal, Miss Bennet,” he offered, his voice as soft as before but no longer tender. Oh, no, not even a little tender. Raw pain was in that voice — pain, suppressed anger, and raging emotions held tightly in check. “I referred to my many mistakes in my addresses. If you might enlighten me as to the details behind your sentiments, I would be deeply obliged.”

Elizabeth bit her lip. She did not want to provide specifics that could only add to his distress, but she did not want to deceive him either. “I think it would be best to leave matters where they are, Mr. Darcy,” she said quietly. “I have no wish to continue a conversation that could only lead to intemperate displays by both parties. I truly believe it would be better to disengage and go our separate ways.”

He stared at her grimly, his mouth compressed to a thin line by the emotions raging behind his expression. “I do not agree, madam,” he said with an edge to his voice that he was unable fully to conceal. “I would rather know how I have offended the woman with whom I hoped to share the rest of my life than to slink off in fear that I might suffer intemperance. Again, I beg you would enlighten me on the reasons for this summary dismissal of my petition!”

Elizabeth looked up, her eyes flashing at the challenge, and her determination to rein in her anger disappeared as she stood up to face him. Very well, she had given him the chance to withdraw, and he had rejected it. Let the result be on his head!

“Then if you so wish it, I will tell you,” she said fiercely. “I have provocations, sir — provocations based on the ruined hopes of a most beloved sister! Can you deny you played a part in most arrogantly separating Mr. Bingley and my sister Jane? Can you deny it?”

Darcy stared at her in dismay, struggling for words. Was this to be the cause of his destroyed hopes? Was the effort he made on behalf of a valued friend the grievance that would divide them forever?

Miss Bennet refused to drop her gaze as he stared down at her, and he could not help but admire her spirit even as disaster washed over him. She hardly came to his shoulder — he towered over her — and yet she met his eye unflinchingly. At length, he sighed and was the first to avert his eyes.

“Is this what you think of me, then?” he asked, in sadness as much as anger. “That I blast the hopes of others due to arrogance? That I disarrange their lives because they are below my station in life?”

“Can you deny it?”

“I will not try to deny I played a part in separating your sister from Bingley, but I will deny that I did so out of mean or base motives,” Darcy said at last. He turned toward the window, his back to the room. He could not endure the sight of those beautiful eyes glaring at him with such anger.

How can I make her see how it seemed to me? he asked himself in desolation; then, his anger rising at being so treated, he wondered, And do I even want to try? But of course he must make the attempt. Surely if he explained himself, she would understand his motivations.

Despite the fact that his hopes had turned to dust in his mouth — or perhaps even because of it — he found that he was no longer strangled into incoherence. He turned to face her.

“Miss Bennet, my actions were based on affection and concern for my friend, much as your anger is raised by your concern for your sister. And until this moment, when you spoke of your sister’s ruined hopes, I believed that I had acted for the best.”

“For the best, Mr. Darcy?” Elizabeth retorted. “What incredible arrogance! I fail to see how it was your part to interfere in any way! You can have no defence to this!”

“You may not give credence to what I have to say,” he responded with some heat, “but I do have an explanation for my actions. Will you hear me out?”

“I again suggest that you leave, sir. This conversation can have no significance.”

“What if your sister had Bingley’s fortune and Bingley had nothing?” Darcy snapped. “Would you not at least feel justified in trying to determine whether his feelings for your sister were true and honourable? And how would you do that?”

Despite her anger, Elizabeth could not help but accept the justice of this statement, and she bit her lip in frustration. Intolerable man!

“Will you hear my defence, Miss Bennet?” Darcy asked again.

Elizabeth struggled to calm herself and at length resumed her seat. “Proceed, sir.”

Darcy again faced the window as misery gripped his heart and he groped to gain control of his emotions. However, he must at least explain himself, slight though the chances of any reduction in her disapproval might be.

“I seek your justice, Miss Bennet, and I ask you to apply that justice to the account I shall give. Some parts of it may pain you, and I beg your pardon for any injury to your feelings. But here is the central point: you charge that I detached Bingley from your sister, and there is some truth in that. However, the issue is more complicated. When visiting with Bingley in Hertfordshire, I soon saw that he preferred your eldest sister to any other lady that we met there. But I had often seen him in love, and I did not at first consider his attachment anything beyond what I had seen before. Then, when I had the honour of dancing with you during the ball at Netherfield, Sir William Lucas unintentionally revealed to me that Bingley’s steady attentions to your sister had led to a general anticipation of their marriage. He spoke of it as a settled fact with only the timing of the event being yet in doubt.”

He turned from the window and looked directly at her. “That was the point at which I decided to act on behalf of my friend. I began to observe him, and I quickly determined that his partiality for your sister was beyond what I had ever previously witnessed. But here is the point at issue: I also observed your sister throughout the length of that evening. I noted that her look and manners were as open, friendly, and engaging as ever, and that she obviously received his attentions with pleasure. But, though I looked most carefully, I could detect no affection on her part to match that of my friend.”

“Jane’s feelings were as fervent as Mr. Bingley’s, however unable you were to discern them!” Elizabeth burst out. “Simply because she does not display them for the amusement of society does not mean that she does not suffer!”

“I must bow,” Darcy said, with a slight inclination of his head, “to your superior knowledge of your sister and admit the possibility — indeed, the likelihood — that I was in error and that your resentment is not entirely unreasonable. But, in my defence, I must tell you that your sister’s countenance and air were so serene that an impartial observer would likely conclude that that her heart was not touched in this affair. While I will admit that I was desirous of believing your sister indifferent, I must state most adamantly that I do not usually allow my hopes or fears to influence my investigations and decisions. I did not believe your sister to be indifferent because I wished to believe it; I believed it because of impartial conviction.”

Darcy paused to collect and organize his thoughts. The next assertions were going to be difficult, perhaps even disastrous, but he had achieved a certain detachment as he crafted his explanations, even as he felt his heart’s desire melting away. After saying too little up to this point, he was now determined to disclose every aspect and consideration, whether it inclined to his benefit or the opposite. He would conceal nothing.

“Another objection to my friend’s attachment to your sister was your family’s lack of connections. But this would be less of a problem for him than it was for myself, and just as I overcame this obstacle, Bingley likely would have done the same. But there was an even greater impediment that remained — both for Bingley and for myself — and that is the lack of propriety displayed by your family.”

Darcy winced as Elizabeth’s expression suddenly darkened. What he would say next could only make it worse, but it was far too late to stop. “I fear this will only increase your resentment, but it must be said. It was the total lack of propriety that your mother and your three younger sisters displayed in almost every public situation that concerned me greatly, for I feared that your mother would influence your sister towards Bingley because of his fortune. I can see that you are angered, and it pains me to offend you, but I said that I would explain myself fully, and I will do so. However, I would like to add that the censure just mentioned in no way applies to you or your eldest sister, for you have behaved at all times with the utmost decorum and civility. I will only add that, based on my observations that evening, I determined to preserve my friend from what I had concluded to be a most unhappy connection. He left Netherfield for London on the following day but with the clear intention of soon returning, and I travelled shortly after to change that intention.”

Darcy glanced at Elizabeth and groaned inwardly as she sat white-lipped in anger. He knew well her fierce devotion to those she loved, and he had just delivered a challenge that could not have been better crafted to inspire her protective instincts.

“I come now to the part in which I acted. Bingley’s sisters were as opposed to the match as myself — although, perhaps, not for all the same reasons — and they joined me in an attempt to detach him from your sister. When we joined him in London, we lost no time in pressing our point. I endeavoured to advise my friend on the evils of such a choice and was able to describe my doubts and argue them pointedly. However much my assurances may have affected his determination, I do not believe it would have been sufficient to prevent the marriage had I not, in all earnestness, assured him of your sister’s indifference. He had before believed her to return his affection with sincere, if not with equal, regard. But Bingley has great natural modesty with a stronger dependence on my judgment than on his own, and it was not unduly difficult to convince him that he had deceived himself. Once that was achieved, it was but the work of a moment to persuade him against returning to Netherfield. Until tonight, I never had reason to blame myself for having made these efforts on his behalf. I may have erred, but it was not done with malice.”

Darcy could not determine the effect of his words. She was no longer gripped with the same anger as before, but her face disclosed no hint of her feelings as she watched him without expression. He was embarrassed, nay mortified, at what he had yet to relate, but he did not hesitate. His situation could hardly be worse.

“There is one part of my conduct in this affair over which I am truly pained, for it does not flow from an honest mistake. That part is that I aided Miss Bingley in concealing from her brother that your sister was in Town. I did not see her, but I knew of it, and Bingley is even yet ignorant of it. It is possible that they could have met without ill consequence, but I judged that his affection for her was not extinguished enough for there to be no danger, so I did what I did and believed it to be for the best at the time. This is the part I have played in the affair, Miss Bennet. It was certainly not my best moment, but I acted to protect my friend on the basis of honest conviction, and though you tell me I erred in my judgment, I did not do so out of any attempt to inflict wanton harm on those involved.”

Darcy was at an end. Exhaustion and despair overwhelmed him as waited to discover the impact of his confessions. He was afraid even to allow himself to hope, but he was incapable of discerning her present feelings as she sat completely silent and still, her head bowed and her hands motionless in her lap. He believed that her rage had dissolved, but what she might be thinking was beyond his abilities to determine.